Subjective Well-being

and the Pursuit of Happiness

The World Health Organisation (2001) defined mental health as “...a state of well-being in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her own community” (p.1)

Well-being and the Hedonic Treadmill

Well-being is defined by two different conceptual approaches, one based on a hedonic approach with emphasis on subjective well-being (SWB) and the other, eudaimonic, which focuses on fulfilment, meaningful existence and personal growth. However, those two models are not necessarily opposed to each other, and could be integrated to improve individual’s well-being (Footnote: Ryan, R. M., Huta, V. & Deci, E. L., 2008, Living well: a self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies. )

As Ladislaw Kovac has eloquently reminded us “We are driven by our permanent hedonic gradient - alternating positive/negative emotions, fixed by genes and early personal ontogenesis…” (Footnote: Kovac, L., 2012, The biology of happiness. Chasing pleasure and human destiny. EMBO Reports. ) Therefore,we all have a subjective experience of emotions in the form of feelings, which may be concealed but influence our cognition and behaviour. Furthermore, he continues, "the notion of happiness as limitless pleasure is counter to a fundamental biological fact - our emotional responses to a pleasant stimulus weaken or even completely cease if a stimulus remains constant."

British psychologist Michael Eysenck likened this relentless pursuit of happiness - to a treadmill (hedonic treadmill), suggesting that people repeatedly return to their baseline level of happiness, regardless of whether their dreams or goals have been achieved or not, or what happens to them in real life. Each person’s happiness set-point is determined 50% by one’s genetic predisposition for happiness, 40% by the habitual, learned cognition and emotional responses, and 10% is due to external influences. Studies (Footnote: Lee et al., 2019, Optimism is associated with exceptional longevity in 2 epidemiologic cohorts of men and women. ) demonstrate that particular variants, or alleles, of the OXTR gene might be linked to stress-related traits and other psychological characteristics. OXTR codes for the receptor for oxytocin, a hormone that contributes to positive emotion and social bonding.

Optimism Between Genes and the Social Environment

Optimism is often misrepresented as extraversion, which is a personality trait or ‘dispositions’, manifested through its multiple facets, such as gregariousness or exhibition of high activity levels. Optimism, on the other hand, reflects an individual’s attitude to the life in general, expectations of positive outcomes either because one can control the outcomes or due to belief that regardless of the success or the hard work invested, the outcome will eventually be successful and hence worthwhile.

Saphire- Bernstein and colleagues (Footnote: Saphire- Bernstein, S., Way B. M.,Kim, H. S., & Taylor, S. E., 2011, Oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is related to psychological resources, Psychological and Cognitive Sciences ) found that people who had 1 or 2 copies of the OXTR gene with an “A” (adenine) allele at a particular location tended to have more negative measurements than those with 2 copies of the “G” (guanine) allele. Individuals with an A allele were less optimistic, showed higher levels of depressive symptoms and had lower self-esteem than people with 2 G alleles.

However, the gene itself neither determines our destiny nor the way we should feel about life. The way we live and how our environment shapes our thinking, emotional responses, and our social interactions, influence how optimistic we are overall. For example, we may move to a new house, get a promotion we always wanted, suffer a loss, and yet after a certain amount of time, we return to our set-point of happiness. After the initial spike in feelings of happiness/sadness, the habituation sets upon us. However, the set point is not neutral, and we may have many of them.

Diener et al. (Footnote: Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. N., 2006, Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist ) study shows that three-quarters of participants reported affect balance scores (positive and negative moods and emotions above neutral. Similarly, even in diverse populations, such as African Maasai, the well-being levels were above neutral. So even if people adapt and return to a previous point, it’s a positive rather than a neutral one.

Although different personality traits may predispose individuals to different levels of well-being, which is partially hereditary, happiness set-points vary from person to person. Moreover, happiness is composed of different factors that contribute to SWB, and different forms of SWB can move in different directions simultaneously. Therefore, we are never ‘absolutely happy’ as it is an abstract concept we create, but both positive and negative emotions are continuously present, hence, one could experience worse health than a year ago and yet experience a rise in life satisfaction.

Furthermore, happiness or SWB are not fixed states but are changeable, depending on multiple factors, such as social changes and/or personal choices. Although studies (Footnote: Kozma, A., 1996, Top-down and bottom-up approaches to an understanding of subjective well-being. World Conference on Quality of Life, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George ) reveal that SWB, like personality, demonstrates some stability over time, the SWB is affected by the way we find the environment rewarding - individual’s personality “fits” the situation (Footnote: Brandstatter, H., 1994, Pleasure of leisure-pleasure of work: Personality makes the difference. Personality and Individual Differences ) and whether our important (intrinsic) goals fit our personality (Footnote: Kasser, T. & Ryan, R. M., 1993, A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology; Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M., 1996, Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. ) Hence, the amount of pleasant affect, unpleasant affect and SWB during university/training years is likely to remain moderately stable, unrelated to future events such as marriage, divorce, finding a job or becoming unemployed. This is because despite changing life conditions, evaluations of specific events are affected by one’s overall level of happiness. However, as our experiences shape our expectations and life goals, our SWB may also adjust, which is contrary to popular opinion why older people may experience an increase in SWB, although less intense pleasant affects (Footnote: Ortega, A. R., Ramirez, E., & Chamorro, A., 2014, An intervention to increase the wellbeing of older people, European Journal of Investigation in Health Psychology and Education. )

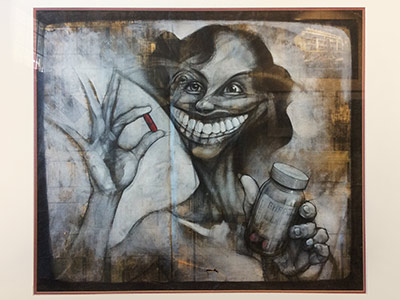

Mood Disorders

However, there is a difference between occasionally feeling down and depression (e.g., mood disorders- Major Depressive Disorder). Experiences of depression and/or mania contribute to all mood disorders, and either can be incapacitating to such a point that an individual sees no point in continuing living. Individuals that suffer from either depression or mania (periods of elevated mood) are diagnosed with – unipolar mood disorder (mostly depression). Bipolar mood disorder consists of both - depression and mania, which are related and may even manifest at the same time (mixed features) (Footnote: Swann, A. C., Lafer, B., Perugi, G., Frye, M. A., Bauer, M., Bahk, W. M., Scott, J., Ha, K., & Suppes, T., 2013, Bipolar mixed states: an international society for bipolar disorders task force report of symptom structure, course of illness, and diagnosis. Am J Psychiatry. )

We must emphasise here, that we all go through grief, moments when we are overwhelmed by sorrow and never-ending pain. When we lose someone from an immediate circle of family or friends, we face anxiety, emotional numbness and even anger and denial. Sometimes we can slip into a major depressive episode, with a crippling feeling of not being able to function. We may even think that we will never experience joy again and then, no matter how strange it sounds, one day we caught ourselves smiling. Those are all normal human reactions.

A happiness setpoint can be applied in clinical psychology to help patients return to their hedonic set point when negative events happen. Determining when someone is mentally distant from their happiness set point and what events trigger those changes can be extremely helpful in treating conditions such as depression

Hedonic and Eudaimonic Ballance

Evidence showing the underlying mechanisms of optimism (Footnote: Scheier, M. F., Weintraub, J. K., & Carver, S. S., 1986, Coping with stress: Divergent strategies of optimists and pessimists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology; Conversano, C., Rotondo, A., Lensi, E., Vista, O. D, Arpone,F., & Reda, M. A., 2010, Optimism and Its Impact on Mental and Physical Well-Being, Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health ) found that optimists tend to use problem-focused coping, seek social support, and emphasise positive aspects of the situation upon encountering difficulties. Pessimists tend to use denial, focus on stressful feelings, and disengage from relevant goals. It appears that those who think positively use more effective forms of coping.

Therefore, based on evidence and research, to increase one’s subjective well-being, a combination of hedonic and eudaimonic views on life is recommended.

Here are a few tips proposed:

- Permit yourself to be human and accept your emotions, such as sadness, fear and anxiety, and your failures.

- Simplify your life but be more engaged. Focus on one thing at a time and reduce multitasking.

- Find meaning and pleasure. Engage in achievable goals instead of focusing on those you feel obligated to do. Spend two hours per week on hobbies and regular quality time with your loved ones.

- Focus on the positive aspects of your life and be grateful. Each day, write down five things for which you’re grateful.

- Increase the effort you put into your relationships. Reach out to others, such as spend more time talking to your children/partner/friends.

- Be mindful of the mind-body connection through exercises, such as drawing, walking, and enjoying music, alone or in groups.

Leave a Comment