Beautiful Forms and Ugly Motifs

Why does beautiful sound awkward in postmodern discourses?

It is unfortunate when we have the paradoxical situation that people in information technology are well aware of the existence of beautiful algorithms while, at the same time, art academics whose job it would be to teach art and, one might assume, also protect their jobs by advocating for the independence of art as a field of intrinsic aesthetic function of communication, often support the populist understanding of beauty as pleasing to the eye.

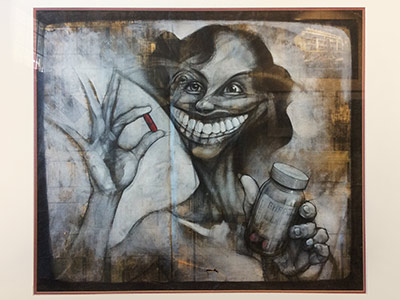

The term beauty of a work of art often sounds a bit awkward because, in the popular language, it is associated with beautiful motifs. For example, a picture of a beautiful woman is usually considered beautiful only because of the beautiful female body depicted. Throughout history, people have had trouble distinguishing an image from the subject matter of an image. In ordinary language, the claim that a work of art is beautiful can refer either to the work of art or to the motif represented, to the experience or the object represented. In postmodern circumstances, the work of art is generally not seen as strictly defined by its framework, so popular speech about works of art usually refers to the experiences of motives and circumstances rather than the immediate experience of the art object. In our time, it is not strange when a discourse about a film ends up, for example, as a discourse about food in crime fiction. Of course, such discourses are not discourses about artistic experiences, but small narratives inspired by the experiences of quotations that are mostly irrelevant to our aesthetic experience of a work of art.

The origin of aesthetic formalism

Many painters throughout the ages were frustrated because people did not see their paintings through their skill, but instead enjoyed what was depicted in their paintings. Throughout history, artists who painted more beautiful women and more beautiful scenes of nature were, therefore, considered better artists. Pictures that represent ugly people are usually recognized as ugly pictures. For a long time, only art experts recognized, for example, Goya's fourteen Black Paintings created between 1819-1823 as beautiful pictures of ugly scenes. When judging art in conversations about art, only the initiated would be able to distinguish art from the subject matter of art.

This confusion of art and objects often happens even in our time. For example, people call heavy metal music violent just because the lyrics present violent content, (Footnote: Recent psychological research published in the American Psychological Association’s journal analysed the emotional experiences of violent Death Metal songs unaware of the difference between aesthetic and referential functions of language. The defence offered was an argument that they did not encounter anyone arguing that the experience of heavy metal music could be beautiful. Based on the wording of their research, one might conclude that, for example, a children’s story Little Red Riding Hood could be blamed for inciting violent crimes. ) or they will deny that horror movies or dramas can be beautiful because of the ugly motifs and disturbing narratives.

In the 18th century, with the establishment of the art market, the art world noticed the problem and began to distinguish the motive of the work of art, what is shown, from the form of a work of art – the way how something is presented. Awareness of the difference in valuing objects and motifs, as well as strong opposition to the long tradition of identifying art with motifs, divine words or depictions of beautiful nature, resulted in the rise of aesthetic formalism. While traditional understandings of art saw art as an activity that has a function beyond itself, such as a social purpose in representing sacred concepts or beautiful forms, formalism emerged as an opposition to this understanding. It follows that the artist's skill is not in the choice of motifs, but mainly in how the motifs are presented. This recognition historically coincides with the recognition of fine art, as a separate way of human activity, and aesthetics - a philosophical discipline that deals with the beautiful (natural and artistic beautiful) and taste.

Aesthetics was founded by Alexander Baumgarten at the beginning of the 18th century as the study of good and bad taste and good and bad art in which the main reference was the concept of beauty. Beauty has traditionally been considered a universal value, just like Truth and Good. As such, Beauty was a necessary property of a work of art and a value superior to other aesthetic properties that could be attributed to an object through aesthetic judgment. In other words, art was considered beautiful by definition. Art objects that cannot be experienced as beautiful cannot be called art.

The argument was that the judgment of taste is a judgment of the senses fundamentally different from the judgment of reason. The pleasure experienced by beautiful objects was, therefore, the pleasure that defines the object as an art object. Objects that aim but fail to evoke a sense of beauty are considered aesthetic failures rather than works of art. The concept of fine art is related to aesthetic beauty, defining an art object as a beautiful object, not what the object represents.

Aesthetic beauty was considered a property of an object made by humans, which distinguishes it as a work of art. As such, aesthetics was the basis for the establishment of art as a separate discipline in society. The fact that in our time we talk about art as a separate area of human experience, and that people have jobs as artists and art teachers, is based on the establishment of aesthetics. Aesthetics asserted that the experience of beautiful artistic forms is a fundamentally different good from the rational experience of truth. Furthermore, the implied aesthetic concepts of disinterested pleasure in beautiful forms and pure beauty were the conceptual foundation without which it would be difficult to imagine the existence of modern art, such as abstract painting or Duchamp's Fountain. In addition to trying to solve philosophical questions about art, aesthetics was part of social discourse, and as such, it influenced artistic practice and articulated the conceptual background of the art world (artistic discourse as text and context).

Before aesthetics, the discourse about art was usually rarely distinguished from the discourse about motifs. After the beginning of the 18th century, people began to talk about art independently of motifs, and beauty was later seen as a quality built into or attributed to art objects. Subsequently, early aesthetics recognized people who enjoy the content of images as having lower taste than those who enjoy form (the way something is presented). In contemporary vocabulary, the appreciation of painted nudes has shifted from the fetishism of pornography to erotics - the metaphysical beauty of the representation of the body. Early formalism did not strive to separate form from motive, but to recognize artistic forms as beautiful aesthetic entities, as special forms that achieve universal values when they are recognized as beautiful. Emanuel Kant called the beauty of form that reaches the metaphysical sphere "pure beauty", and the pleasure in form (pleasure in the way something is presented) in the aesthetic unity with the motif (what) as disinterested pleasure. The experience of beauty is pure (disinterested ) only if the pleasure is in the experience of a beautiful art object, and not in the experience of a possibly beautiful represented motif.

The concept of pure beauty was later challenged as an idealist concept with arguments that it is difficult to imagine excluding empirical experience from the experience of a representative work of art. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to distinguish the conversation about a mirror from the mirror reflection. We consider the ability to differentiate the representing object from represented as a heritage of our civilisation. The fact that we can say that a mirror is beautiful without seeing our reflection in it, is strangely ignored by postmodern contextualists. Kant's understanding of pure beauty in art developed into a concept that we, at this time, call the "syntagmatic" character of a work of art, where the meaning of the representation is constructed in the how, not the what. The subsequent criterium of an aesthetic value is not related to some degree of verisimilitude, to the degree of how lifelike is a painting, but to the experience we may have when viewing the painting. The quality of this experience determines the aesthetic value. When our appreciation excludes the form, we seek to communicate with the represented rather than the aesthetic whole. By focusing on noticing reflection, we fail to see art. If we see pornography where society sees erotica, our taste obviously limits us from experiencing works of art.

On that basis, our contemporary culture distinguishes art from kitsch experiences. Likewise, the difference between the experiences of pornography and eroticism is established by the aesthetic formalists who opposed the same mystical confusion between the object and its representation, between the image of the pipe and the actual pipe.

Great Theory of Beauty and abstract painting

At the time of the beginnings of classical aesthetics, artists perceived beauty as a property of the art object. Each work of art had perceptible qualities dependent on the medium such as 'line', 'tone', 'colour value', and 'colour' in the image. These elements were seen as composed into an artistic whole, a unity called 'composition' organized according to the principles of proportion, harmony and symmetry of forces.

The composition had to balance the elements, as forces in the field, according to the "unity in diversity" principle. For Aristotle, the implied integrity of the art object is a necessary condition of a beautiful form. The conceptual background will become known as the Classical or Grand Theory of the Beautiful. In our time, laws of good forms, such as the golden ratio, recently rediscovered in cognitive psychology, are taught as the secret knowledge of art studios about the principles of beautiful forms. Indeed, we could talk about these rules in psychological terms as conventions that define beautiful patterns and avoid the universalist traps of idealist philosophy.

Following the theoretical framework of good taste and the advent of photography, which made visual representation a matter of technology, visual artists in the last century were encouraged to play with artistic form and media and ultimately to completely neglect the representation of content. That is how we ended up with artworks without motifs. Following the principles of music, an art that usually lacks motives, visual art tended to open up the potential of the play of imagination and intellect to the extent that it became completely open to interpretation. Following ancient principles of formal organization and metaphysics of universal order, visual art ended up being pure form, allowing viewers to add content (transcendental meaning) if and when they wanted. The idea that art can be beautiful without any reference, just like the flowers in the field, is a legacy of modernism explained by the Kantian idea of pure beauty.

Both Plato and Aristotle understood art as representation, but Plato saw representation primarily as a representation of principles rather than appearances; the representation of the particular (nature) had less value than the representation of the universal (ideas represented by nature). Abstract painting, therefore, is explained as a painting that does not represent any content and strikes us with the rules of beautiful structure freed from the constraints of any figurative reference. In the classical theory of beauty, the rules of the beautiful organization were seen as rules of the divine organization. The rules of fine art composition, which appear to us through the work of art as a convincing aesthetic whole, define a beautiful abstract image. It has been shown that a painting can be experienced as beautiful without beautiful women or beautiful nature, only by following the ancient rules of a visual organization recognized in beautiful nature as universal principles of natural and artistic unity.

Freed from the constraints of figurative representation, visual art was suddenly free to explore its bare nature. Highlighting the conceptual character of the organization of the work of art has revealed that the essence of art may not be representation at all (theory of art as an expression), that beautiful communication of meaning is the essence of artistic beauty (theory of art as communication) or that the work of art should remain open and resist conceptual closure (theory of art as an open form).

Arguments against beauty in art

In ancient Greek, the term aesthetic was associated with sensory perception and was introduced into philosophy to emphasize the immediacy of taste versus reason. In popular understanding, experiencing the beautiful is still a matter of emotion, while meaning is a faculty of the mind. It is nicely separated from meaning like the passive percept from the active concept. Following the same linguistic heritage, beauty is still often understood as a property of an object that is attractive to the eye or as a direct consequence of perceptual pleasure.

This connection between perception and beauty is deeply embedded in language. It is a misconception that art objects, viewed through perceptual pleasure, can be beautiful, while ideas cannot. And this is the basis for why it seems reasonable to claim that, for example, Goya's painting Third of May 1808. and Duchamp's Fountain are not beautiful. First insists on artistic content as a concept (political statement), and second, on the concept of context that defines the object as an artistic object. It seems that neither concept nor context in our recent linguistic realms is remotely related to the feeling of beauty.

In the second half of the last century, some young theoreticians, ignoring the historical discourse of art, began to question why we need beauty as a part of art if art is a matter of meaning, not a beautiful presentation. In their understanding, which followed the Cartesian dichotomy of passive perception versus active reason, an object or statement cannot be, at the same time, meaningful and beautiful. Repeating the ancient confusion, illustrated by the anecdotal inability to distinguish between a real pipe and a picture of a pipe, they often associated artistic beauty with beautiful motifs, that is, with beautiful women or beautiful nature depicted. They never asked why ugly forms were considered beautiful art throughout history. In their contextualist arguments, it is impossible to judge a work of art without reference to what is shown. This is why the meaning of art in postmodern discourses often ends up with linguistic logocentrism, judging linguistic social references instead of works of art. When facing Magritte's This is not a pipe, they are more likely to end up talking about the depicted pipe and the social consequences of smoking rather than enjoying the immediate experiences of the painting. As a rule, they fail to understand the pun aimed at mocking the inability to distinguish an object from a representation of an object.

Most of the postmodern criticism of aesthetics is based on the popular notion that in our-time art is no longer concerned with the beautiful but with the meaningful. Therefore, the argument is that Goya's painting, as well as Duchamp's Fountain, should be seen as conceptual statements and therefore cannot be considered beautiful. Such arguments are founded on false premises. Now, we know that the Cartesian dichotomy that separates passive perception from active concept is false and that something must always be seen as meaningful before it can be experienced as beautiful (Gestalt psychology). In this sense, in contemporary aesthetics, beautiful is no longer opposed to meaningful since both are consequences of the same cognitive processes. Rudolph Arnhem called it visual thinking. Certainly, we can speak similarly about music.

The concept of beauty has historically been one of the most controversial concepts in philosophy. One of the main reasons for numerous misunderstandings was the deeply rooted differential relations of language separating and subjecting emotions to intellect. Nevertheless, in the Greek language, the word kalos is still used to denote beautiful forms and beautiful ideas. Therefore, due to the unchanged linguistic background of the word beautiful, it is much easier for the Greeks to understand contemporary aesthetics. It is similar in some other European languages. In today's aesthetics, we no longer see beautiful as a property of objects that results from passive perception. In many languages, people didn't need to stretch the meaning of the word beautiful because it was already used in a way that allowed ideas to be beautiful and, therefore, smoothly allowed the aesthetic perspective to shift from aesthetic object (aesthetic formalism) to aesthetic process (phenomenology) and, finally, to the social context (poststructuralism).

It might help if, for heuristic purposes, we temporarily imagine that the translation of the word beautiful in English, as is commonly used in contemporary aesthetics, is wow instead of beautiful. In this way, for argument, we could temporarily exclude the connotations of the term beautiful to kitsch objects. It might be easier to understand the concept when applied to describe the experience of modern art, forms perceived as beautiful statements. So, nowadays, when we say that art is beautiful by definition, we can imagine saying that art is wow by definition. Something has to be wow to be considered art.

Arthur Danto's criticism of aesthetics, which points to the impossibility of explaining Duchamp's urinal as an aesthetic object, rightly aims to criticize the extreme formal school in aesthetics - the one that based aesthetic judgment solely on the formal properties of the aesthetic object. Proponents of abstract painting, for example, often claimed that only forms without motifs and any references to reality should be considered real art objects. Against such aesthetic normativism, Danto pointed to the fact that what makes Duchamp's urinal an art object is not in the urinal itself (in its form). It is not form that makes Duchamp's urinal a work of art. That is why we do not talk about Duchamp's urinal as a beautiful object, but about the gesture of placing it in the context of art objects as a wow gesture. Indeed, Danto's later analysis of the concept of beauty in art suffers from an inability to separate the realm of representation from physical reality, which is symptomatic of a range of postmodern writings that fail to frame the subject of discussion. Arguments about the alleged abuse of traditional beauty with avant-garde ugliness miss the point that artistic beauty was not in the motifs, but in the mythopoetic experience of the play of intellect and imagination recognized as experience of beauty.

At that time, aesthetics was already shifting the focus from art objects to ways of communication - to the experience of the text as a tissue of quotations. Later criticism of aesthetics, as an anachronistic theory of art that insists on the concept of beauty, often misses the point that the aesthetic thought of our time does not ignore the fact that modern art is based on meaningful and not on representation of beautiful, but usually uses the term beautiful including the experience of the meaningful (like the wow experience).

The experience of the metaphysical (transcendental) layer of the work of art, as Ingarden and Hartmann posited it, (Footnote: Roman Ingarden (The Cognition of the Literary Work of Art, 1936) and Nicolai Hartman (Aesthetics, 1953) followed Kantian phenomenology in aesthetics by framing the experience of the artistic metaphysical or transcendental meaning as a distinct stratum of an aesthetic experience. ) was, therefore, from the beginning of the 20th century an experience of beautiful ideas. In this context, we could hypothetically call it wow instead of beautiful. Of course, after Saussure and semiotics, it was clear that the ideas that define the experience of beautiful objects are a matter of linguistic connotations. Art objects, as well as the experience of beauty, became defined by the dynamism of the cultural context, just as the reading of Duchamp's Fountain affirmed. Postmodernist positions commonly ignore the distinct experience of the aesthetic object and reduce art to politics by arguing that art is what the art world says art is (Danto's and Dickie's institutional theory of art). Indeed, it is one among many accounts of art failing to address art at all, and certainly not final. (Footnote: Arthur C. Danto, in What Art Is, for example, attempted to avoid engaging with aesthetics by insisting on naming his efforts a theory of art. Subsequently, he failed to realise that what he discovered as the essence of art in “embodied meanings” was the core problem in art theory since Plato’s aesthetics. Plato criticised the principle of the representation of nature in visual arts since, in his view, the highest goal was in the representation of universal ideas. Arts aiming at representing nature were considered as works of epistemically and ontologically lower value. It was rarely the case in history of thinking about art that it was related to the senses exclusively and excluded meaning, just as it was rarely the case that works of art were about “grasping the intended meaning they embody” exclusively (intentionalist theories of art). )

Regardless of all the criticisms of aesthetic concepts and ubiquitous academic relativism, there is still no valid argument that would exclude the experience of beautiful (wow) from the experience of art. There is no reason to deny the possibility that someone can see Goya's Third of May or Duchamp's Fountain as beautiful (wow). In the same way that ancient Greek tragedies were perceived as beautiful forms even when they presented disturbing content, we can say that contemporary horror films and paintings depicting terrible real events, such as Picasso's Guernica or Goya's Third of May, can be experienced as beautiful works of art. In the history of art, there have been many examples of ugly motifs. Artworks that present ugly motifs do not make the artworks ugly as long as we can distinguish the what from the how. If the mode of artistic composition determines our wow experience, then we can talk about beautiful art despite ugly motives. So ugly can be beautiful and beauty can still define art.

People no longer feel the need to claim that art is "good", but, in an aesthetic sense, a work of art is assumed to be good, beautiful and a true statement. Certainly, we can live without archaic expressions that usually refer to absolute values such as truth, goodness and artistic beauty, but such intellectual reductionism would make culture a miserable shadow on the wall.

It is unfortunate when we have the paradoxical situation that people in information technology are well aware of the existence of beautiful algorithms while, at the same time, art academics whose job it would be to teach art and, one might assume, also protect their jobs by advocating for the independence of art as a field of intrinsic aesthetic function of communication, often support the populist understanding of beauty as pleasing to the eye.

The argument that historically art has always been about meaning as universal statements and experiences using particular compositions and that beauty was like a code defining a certain way of communication is still not broadly understood. Not even the argument that according to modern cognitive psychology, 'immediate appreciation' is necessarily a cognitive experience can convince some people that ideas and algorithms can be beautiful and that there is absolutely no reason to remove the experience of beauty from the experience of art. The term beautiful has always been used to describe the experience of art objects as aesthetic unities, rather than their possibly beautiful motifs or references. When we say that the picture is beautiful, we do not mean to say that the woman depicted is beautiful, as is often interpreted by contextualists. When we say that a film is beautiful, we are judging our experience of the film as an artistic unity of form and content, our experience of the entire statement, and not of a single quote that can be observed on its own and interpreted as a beautiful detail and potentially the subject of some socially critical examination. We cannot deny the possibility of discussing the social circumstances surrounding the making of the film. But we also cannot avoid recognizing films as art forms that we can talk about without resorting to quotations that are outside the overall mythopoetic naming. It is about the intellectual ability to distinguish film from the filmed as a subject matter, a painting of a pipe from the represented real pipe.

It is not difficult to understand why people of our time might find the aesthetic use of the term beautiful inappropriate. After the fall of Greenberg in the American art world, kitsch forms were freed from the stigma of bad taste and are often recognized as beautiful. (Footnote: Postmodernists accused Clement Greenberg, an American art critic and a proponent of the continental formal school of aesthetics, of favouring abstract expressionism. Indeed, the opposition to the dogmatic aesthetic normativism of the eighties, and subsequent cultural antielitism, opened the doors to the populist interpretations of postmodernism by an antiaesthetic movement, the global kitsch market and the global corporate overtaking of fine arts culture. ) Postmodern discourse insists on avoiding value judgments of taste, and the kitsch production is defined by the desire to be recognized as art. The result is the mass production of kitsch artifacts sold as beautiful objects and the corporate takeover of culture in the name of a free market for beauty goods. Growing up in a society where the term beautiful is usually associated with kitsch forms would subsequently define the former artistic avant-garde as an opposition to forms with beautiful motifs. In this sense, we can understand contemporary arguments against beauty in art. (Footnote: Gianni Vattimo in “Beyond Interpretation”, for example, argues that, “idealization of beautiful and ethical life” became impossible because the “classically perfect identification between content and form, and the completeness and definitive quality of the work, is anachronistic, illusory and in the end positively kitsch (nowadays only merchandise promoted in advertising is presented in this way)”. Pointed out by Thorsten Botz-Bornstein in “The conversation” forum argument. ).

In such circumstances, art will necessarily be seen as subversive to the sugary conservative beautiful motifs and forms that were once recognized as kitsch. In our time, the main problem is not the polysemy of the term beautiful but the omnipresence of kitsch disguised as art. Kitsch is no longer recognized as kitsch, but as a commodity that becomes part of the culture, and some artists often describe kitsch as irresistibly beautiful. So, as kitsch is increasingly recognized as beautiful, an artistic practice increasingly insists on avoiding association with beautiful. That explains the fact that, currently, far more people would agree with the claim that a work of art has to be wow than beautiful.

The term beauty has a long history, much longer than art... Art comes from a Latin word that means skill (in creating beautiful objects) In the 17th century, it was semantically anchored in a meaning similar to the modern one. There is a long history of the terms beauty and beautiful in such a way that they can function smoothly in judgments like beautifully subversive. This kind of flexibility in which beautiful can be assigned to ideas is our linguistic heritage. Arguments that, for example, Picasso would never have seen Guernica as beautiful do not hold up. By the time Picasso painted Guernica, Kant's understanding of pure beauty and its applicability to the modernism of the art form was as much a part of European linguistic culture as was the common ability to define the topic of any conversation. The habit of discussing art by discussing the depicted motifs, or the artist's girlfriend who committed suicide by jumping from the fifth floor, is a rudiment of a long legacy of discourse captured by non-artistic functions. At the beginning of the 18th century, criticism of such an inability to rationally focus on the topic of conversation about art caused a revolution that ended with the modernist conception of fine art, as well as the emergence of aesthetics as an attempt to think about the experience of beautiful forms without exclusive reference to represented.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment