Beautiful in Art

Beautiful as Meaningful in Contemporary Aesthetics

In the same way, as in our time, we can not speak about "truth" and "good" having universal validity, we can not speak about "beautiful" as the issue of an essentialist consensus or a universal "common sense". On the other hand, we can not deny the existence of the "wow" as sometimes shared experience when facing some works of art. We can avoid calling it the experience of "beautiful" but, then, we will be abandoning our linguistic tradition and yielding to the kitsch industry linguistic reductionism.

In our time, when we talk about art, we no longer understand beauty as limited to the phenomenological layer of the work of art, to the beautiful things displayed. It is clear from Emanuel Kant that talking about artistic content and ignoring form does not say anything about art, just as the experience of the beauty of the depicted nature does not have to be related to the experience of the work of art (Footnote: By following lord Shaftesbury's understanding of disinterested pleassure Kant distinguished aesthetic pleasure, as the pleasure one may have in relation to the work of art, from the empiric pleasure, as the pleasure spectator may have in represented motifs. ). We do not need to recognize a beautiful object represented in a picture to be able to say that the picture is beautiful. For example, a picture of an ugly house or an ugly person can be a beautiful picture, since our judgment is related to the picture, not to what is depicted. When we judge an artistic painting and say that a painting is a beautiful work of art, we do not mean that the painted motif is beautiful, but the painting itself. We can say that a picture can be a beautiful picture of an ugly motif. Furthermore, such beauty is no longer tied exclusively to "the pleasure of the eye", but also to the pleasure of pondering the meaning. The experience of 20th-century art affirms that artistic beauty has never been a pleasure only for the eyes but, above all, an experience of objects offered to our free play of imagination and intellect..

Aesthetic Experience Beyond Empirical Pleasure

A work of art is a beautiful object when we have an aesthetic experience with the object, with "how" something is depicted, not with "what" is depicted. Kant called it a disinterested pleasure. The pleasure we experience by contemplating a work of art, the free play of imagination and intellect, is not necessarily related to empirical pleasure, to pleasant memories of previous experiences triggered by the motif, but primarily to the way the motif is composed, to the meanings attributed to the aesthetic whole..

The existence of abstract painting illustrates the understanding that art can completely skip the phenomenological layer (represented content) and still be beautiful. A painting is "a flat surface covered with colours arranged in a certain order." (Footnote: “Remember that a picture, before being a battle horse, a female nude or some sort of anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.” Maurice Denis,1890, Le spiritual dans l’art, essay published in the review ’Art et Critique’, Cited in Bouillon, Jean-Paul, 2006, p. 21.). When there is no figurative content, we can still experience the beauty of form. So, we do not say that a work of art lacks beauty if it does not represent anything. The form itself, the way how the composition is organized, can be experienced as beautiful. (Footnote: Of cause, here we speak about abstract painting as non-figurative painting. “Abstract” is a term chosen to signify non-figurative art. It has unfortunate connotations pointing to the process of figurative abstraction but, in fact it is signifying non-representational paintings, artworks without figurative reference. As such the term “concrete” would be far better term describing what the abstract painting is about.)

In our time, in terms of Semiotics, we might say that in art a syntactic principle of the artwork organisation ("how") is often more significant than semantic ("what"). In this sense, on behalf of our time, Marshall McLuhan argued that "the medium is the message." and pointed to the historical problem of confusing form and content (Footnote: In “Understanding Media”, McLuhan described the “content” of a medium as a “juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind”, Routledge, London, 1964. That is, content of the message is what is often experienced as what the medium itself is about. Certainly, in terms of classic cartesian form-content distinction, for the aesthetic function of communication, form of the message is far more significant than content. By following aesthetic formalism McLuhan pointed to the fact that people are often not able to judge about medium without references to content.) That is to say, when judging about art, throughout history people had difficulties distinguishing artwork from motifs depicted and commonly confuse depicted pipe with a real pipe. Instead of judging the painting, they judge the motifs depicted even when the meaning of the artwork is obviously related to the way the motif is painted. From this, it follows that the meaning of the work of art is never in quotations but in the experience of the aesthetic whole as the unity of what and how. The modernist understanding of art, after the cognitive revolution from the middle of last century, implies that aesthetic experience (the experience of the work of art) is a cognitive experience. Therefore, experiencing beauty in art is not only a question of emotion, as interpreted by classical pre-modern aesthetics but also a question of the intellect. (Footnote: See, for example in “ Visual Thinking ” by Rudolf Arnheim, 1969. Gestalt Psychology reveals visual perception as a cognitive process, hence ending the cartesian “ passive percept - active concept ” distinction and redefining the experience of “beautiful” as a specific kind of cognitive experience.)

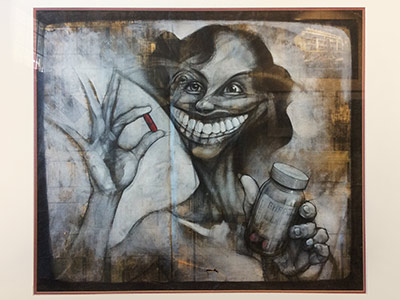

The representation of ugly forms, just like the lyrics of a heavy metal song describing violence, can be experienced as beautiful. It is not to suggest that depicted violence is beautiful, but that the experience of the unity of form, despite the ugly motives, can reach a metaphysical significance and therefore appear as an experience of beautiful form. (Footnote: In this context, I am referring to Ingarden's and Hartmann's phenomenological aesthetics and the observed stratified character of artwork reception. According to these understandings, the experience of beauty is based on the experience of the “metaphysical” or “transcendental” layer of artwork. Abstract painting is, for example, attempting to reach the metaphysical layer by skipping the phenomenological layer (representation) )

Ugly and Meaningful as Beautiful

In aesthetics beautiful is not synonymous with pretty but rather corresponds to the aha or wow effect recognized by our-time psychology. Ever since Aristotle we acknowledge catharsis as an aesthetic category assuming that the ugly and tragic can be experienced as beautiful. In the history of art, there are numerous examples of forms that are ugly (as representations of ugliness) but, as in all works of art, they evoke aesthetic experiences. We can say that ugly motifs and truths can be painted beautifuly, just as modern horror films can be beautiful in an aesthetic sense. In the same way, arguments that in our time beautiful is no longer necessary in art because, for example, a Duchamp's readymade "Fountain" is essentially an ugly urinal, miss the point. Beautiful in art was never related exclusively to motifs but to the overall aesthetic naming. When we say that Duchamp's Fountain is beautiful, we do not mean the urinal shown, but the Fountain implied. We speak of Duchamp's Fountain as a beautiful artistic gesture (in sense of a meaningful gesture, a gesture that makes aesthetic sense). Playing with the medium is what both a metaphor in language and the aesthetic function of art are about. The medium (the form) of Duchamp's Fountain is not the urinal but the context set by the political status of the work of art.

In our time we talk about aesthetic function of language and communication (after the Prague Linguistic School). We acknowledge that aesthetic experience is integral to our experience of the world. One does not have to be an aesthete to appreciate aesthetics in everyday life. We know that beautiful design sells cars and that mathematical solutions can be more or less beautiful. Art is basing its existence on experiences we recognise as the realm of the aesthetic function. Beauty is, therefore, a necessary condition of art. But not the beauty understood as an essential property of pretty objects, like pretty flowers or sunsets. We use the term beautiful in an aesthetic sense to define the wow experience, the moment we recognise something profound in naturally beautiful objects or while communicating with a work of art, the moment of bliss described by Maurice Merleau-Ponty as, "seeing more with the object than seeing the object itself". Following Kant, we say that aesthetic beauty is not related to empirical beauty. The motif of a painting may be beautiful in itself, but this is not the artistic beauty we are talking about when we talk about beautiful art. Artistic beauty is related to the experience of seeing with the object rather than seeing the object.

It is, therefore, wrong to say that "art does not have to be beautiful" and that in our time "beauty counts for little in the judgment of works of art", as is often stated by people who confuse "beautiful" with "pretty" and insist on the contextualist assumption that artistic motifs must be beautiful for art to be beautiful.

The aesthetic function is what distinguishes art objects from other objects. Art is beautiful by definition. Art is beautiful because it has to be wow to be recognised as art. And wow itself is what we used to call beautiful when we evaluated an art object and expected other people to agree with us. Of cause, in this sense, we are talking about the beautiful as a meaningful experience as it was used by the ancient Greek kalós (καλὸς) and not as a hedonistic superficial pleasure for the eyes of the Augustinian voluptas. The idea that beautiful excludes meaningful is based on an outdated cartesian dichotomy that opposes percepts to concepts. This understanding insists on the existence of the passive world of the senses subjected to the active powers of the rational mind, where the experience of beauty is a mindless pleasure comparable to the experience of pornography. Thus, the assumption that perceptual pleasure excludes meaning, disputed by contemporary neuropsychology, and the anecdotal inability to distinguish between artistic forms and motifs, as indicated by Magritte's This is not a pipe, are the main reasons for contemporary arguments that art is no longer beautiful.

Of course, the intentions to avoid the term beauty in the designation of contemporary art is also encouraged by contemporary mass kitsch production of pretty commodities and entertainment marketed as beautiful and as art. Just as we do not intend to proclaim the end of art because of ubiquitous entertainment, there is no reason to abolish the term beautiful because of the kitsch infestation of culture and the kitsch appropriation of the term beautiful.

Beautiful versus pretty - art versus kitsch

The basic argument of this text is that it is not reasonable to confuse entertainment with art as well as pretty with beautiful, which often seems to be the case in contemporary texts about art. The global corporate appropriation of the concepts of beauty and art, follows the global crisis of values symptomatic of the postmodern condition. The fact that beauty was throughout history traditionally seen as an ultimate value does not mean that, in the name of anti-essentialism, we should abolish the use of the term together with terms such as truth and good. Just as in our time, we cannot speak of truth and goodness as universal values, we cannot speak of beauty as a matter of essentialist consensus or universal common sense. On the other hand we can not deny the existence of the wow effect as a sometimes shared experience when facing some works of art. We can avoid calling it an experience of the beautiful but then we will be abandon our linguistic tradition and indulge in linguistic reductionism supported by the kitsch industry. Our culture, philosophy and aesthetics have given us clear tools to distinguish forms that are pretty but pretend to be beautiful. We call them kitsch, not art (Ludwig Giesz). When we talk about the difference between kitsch and art, of cause, we are not talking about them belonging to the same kind of experience to allowe us to compare them by the same standard. The qualitative difference between kitsch and aesthetic experiences is often ignored by populist art discourses. However, this question is beyond the scope of this brief review.

It should be clear by now that we use the term aesthetics to name a philosophical discipline, not as a term synonimous for beautiful or for experiencing beautiful objects. Therefore, the claim that it is not possible to learn and teach aesthetics and refine tastes and aesthetic judgments is wrong unless one insists on the nonsensical anti-aesthetic statement that "tastes are not to be discussed." As long as we agree that there are different tastes, there is no valid reason why we should not discuss tastes.

We can not say that all modern art is beautiful. There is nothing beautiful in Duchamp's "Fountain," in Picasso's Cubist paintings or Bacon's Pope's. Modern artists often made it clear that art is not supposed to be beautiful. The philosophy of our time is avoiding the term "beautiful".

I am aware of beauty sceptics in the philosophy of art. They often assert that “beauty” is subjective and simply too vague to be used in philosophy. So, instead of investigating the rich etymology and facets of possible meanings defining the evolution of art discourse, they suggest abandoning the word altogether. Even if this could be possible, the world where we could abandon polysemic words would be sad, indeed.

We do not stop using the term "atom" because we no longer see it as indivisible. Logical positivists and philosophy sceptics would like to change language because natural language does not allow the development of neat conceptual systems. I never considered the logocentrism of “beauty sceptics” seriously, and I can not agree with anyone who does.

Some philosophers do not feel what art is about and do not realise that polysemy and subsequent persistent escaping from attempts of analysis is the nature of art, similar to creative language. Confusing content with form and recognising creative facets of language as linguistic obstacles, rather than potentials, is the nature of logocentrism. The will to establish neat conceptual schemes often reveals an inability to distinguish mythopoetic from propositional functions of language.

Arguments that contemporary art is not beautiful subsequently suggest that we can rarely see “realistic” representations of beautiful motifs in contemporary art. In our time, even some fine arts academics speak about “aesthetically flawless” artworks referring to technical verisimilitude. The "lack of beauty" in contemporary art is referring to the lack of beautiful representations. The term aesthetics in art is often seen as related exclusively to motifs and technical skills in verisimilitude.

It is not strange why people, not able to see beauty in forms without content, would have difficulties understanding Kant’s concept of pure beauty. They do not realise that pure beauty in art was never the issue of beautiful motifs or assertive resemblances. In our time, it is popular to speak about visual art as a visual text. People chasing neat rational schemes in the art will never be able to see the beauty in the visual text that is elegantly escaping analysis and making the avoidance of the closure the specific difference of the artistic experience.

A necessary condition of an art object is its belonging to a certain class of objects with the ability to trigger an emotional response. We could call the response “wow” if you prefer. As long as we agree that this particular kind of response is specific, although not exclusive, to art experience, it is irrelevant how we name it. Besides the immediate linguistic function to define our relationship to the object as an aesthetic judgement, which one may see as passé, the word also has the function of linguistic bracketing, just as a code word in computer programming. To be able to see something as art, we need to overcome the entropy by applying an enabling structure (W. Iser) or a System code (Umberto Ecco). It adjusts our cognitive system to a particular class of experiences and allows us to experience readymades as aesthetic objects.

By framing the experience as beautiful we define it as a specific mode of human experience, different from other experiences but commonly shared within a society. Ancient Greek language recognised it as the realm of mythos, essentially different from the realm of logos. In modern times, the term beautiful took that important linguistic function of framing the class of objects as the realm of metaphorical language. No one can deny that the context giving meaning and significance to the Duchamp’s urinal was the context of beautiful objects (an art exhibition). Without the context of beautiful objects, there would be no Duchamp’s “Fountain.” The “Fountain” was defined by its belonging to the class of objects which may be experienced as beautiful, even though by itself the object may not be seen as beautiful. Of cause, we no longer speak about the beautiful being an immanent property of an object. We speak about experience in the relation to the object. What is artistic in Duchamp's Fountain is not the object itself but the gesture; by saying that the Fountain is beautiful, we are not claiming that the urinal itself is beautiful, but the concept of placing it within the artistic context. When saying that a conceptual work of art is beautiful we are saying that the idea is beautiful. We recognise the pun as a wow statement.

In our time we no longer deny that ideas can be beautiful.

I know for sure that in mathematics there are more and less beautiful ways to come to the result. Beautiful solutions are elegant and inspiring, while boring and predictable solutions are not beautiful .

Leave a Comment