What does it mean?

Art spoilers or advancing in opera appreciation?

.

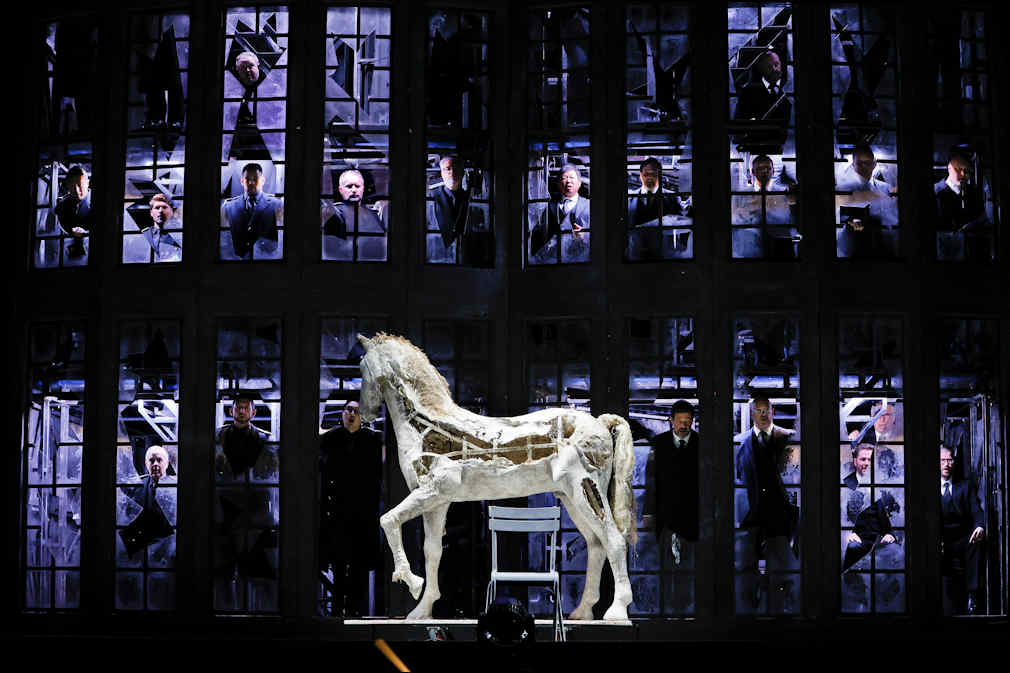

In the article on Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin opera by Opera Australia, “The singing was great – but what was it about? Why opera companies should explain themselves better” in The Conversation from May 26, 2022, Peter Tregear argued that the Wagner opera production’s symbolism should have been explained in a program essay. According to him, Opera Australia failed to seize the opportunity to educate its audience. Opera’s public role “after all, should not be just to entertain us, but also to inform and at times (…) -challenge us.”

Entertainment and Aesthetic Experience

The argument that opera’s primary function is to entertain us is highly questionable since it places experiences of art and experiences of entertainment in the same category. Saying that art is entertainment fails to say anything about art. It asserts that art is related to some kind of pleasure but does not distinguish between, for example, game playing and enjoying an opera performance. Furthermore, it is emphasising a hedonic character of an experience which would likely exclude experiences of traditional tragedy, horror films and numerous fine art exhibitions that could hardly fit into the category of entertainment experience.

The notion that, when we speak about art, we speak about objects created for no other purpose but the play of imagination and understanding is far more useful. (Footnote: In Kant's terms: The free play of cognitive faculties - imagination and intellect. ) It explains why, for example, we do not consider footballs and butt plugs works of art. It might be difficult to argue that football and butt plugging requires intellectual engagement. So, it is reasonable to understand the suggestion that art objects are created for the specific kind of pleasure related to the intellect as excluding all other pleasures commonly referenced by the term entertainment, the activities resulting in pleasure but that do not assume such intellectual engagement. Recognising art as entertainment was a postmodernist reaction to the unfortunate long tradition of elitist art academism, the cultural hegemony which asserted that enjoying fine art required a sophisticated taste, developed as a privilege of ruling classes. Without a doubt, the pushing of entertainment, as an experience of art, aimed towards denying the value-difference between canonical and foral arts (Footnote: Distinction used by Boris Uspensky in A poetics of composition: The structure of the artistic text and typology of a compositional form, (1970). Foral is also commonly translated as non-canonical or folk. ) and democratisation of culture. But, the good intentions went too far by collapsing art and entertainment into the same category. Likevise, muddling the distinction between art and applied art or entertainment in a way to imply that the difference between experiences of art and but-plugging is the issue of perspective is a pseudo-intellectual nonsense.

Postmodern discourses are habitually framing entertainment experience as a sort of art appreciation in the supposedly egalitarian liberal culture and failing to recognise the substantial difference between art and entertainment, between experiences of Lohengrin opera performance and butt-plugging. (Footnote: Of course, when judging tastes and experiences in a postmodern context, there is no difference between the same-scale value of appreciation implied by traditional aesthetics, where superficial experiences of entertainment were considered inferior to profound (deep) aesthetic experiences. The problem was that postmodern critics of metaphysical superficiality in aesthetics commonly fail to consider that aesthetics could have been distinguishing between qualitatively different experiences rather than by Platonist continuum (where experiences were seen as substantially identical and, hence, allowed the measuring by the same scale). ) They disregard the fact that contemporary notion of fine art was based on establishing the qualitative difference implied by the notion of the difference between ritual empathy and carnival transgression, which is framed by aesthetics of the 18th century as the difference between disinterested and empirical pleasures. (Footnote: Beautiful objects with a purpose other then art-experience could have been considered craft, but not art. In Kant's understangding desinterested pleasure is the pleasure in the contemplation of the object made for no other purpose but the purpose of the experience of contemplation, while the empirical pleasure is related to the pleasure in what is referenced or re-presented. We could say, regarding a painting for example, that the former is focusing on the object and the pleassure in how a painting is painted, and latter is focussed on the reference - on what is depicted (motifs and content recalling pleasant memories or other outer purposes, such as religious, political or ethical meanings or sentimental evocations). Indeed, after the establishment of the notion of fine art, the pleassure in the referenced was traditionally considered as a failure to engage with art. )

We could say that the recognising of the role of art in challenging audiences, implied by Tregear's argument quoted in the introduction, corresponds with the views of art that distinguish aesthetic experience as a play of intellect and imagination framed by traditional modernist aesthetics. On the other hand, the implied suggestion that challenging the audience is predicated on the linguistic explanations of the symbolism is the nature of contextualist understanding of art that could in our time be seen as being on the track of the arrogant and patronising institutional attitude towards the art public, denying them the ability to have an aesthetic experience without kitsch foundations in linguistic platitudes. The implied suggestion is: We know that Australian opera public is ignorant, so we should also educate people by program essays to supply the knowledge necessary to correctly appreciate the opera symbolism. It is on one hand collapsing the aesthetic function of art to referential function of propositional communication and, on the other, insisting on value judgements driven by the Platonist notion of the perfect transparency to the anchored meaning (logos). So, what began as poststructuralist attempt to avoid Platonist obsession with presence (fixed meanings) and value judgements of experiences and tastes, ended, in the language of contemporary postmodern artworld institutions, as a modified version of traditional Platonism.

Experience vs correct descriptive knowledge

My writing aims to assert that the challenge is not an incident but the defining property of an aesthetic experience. Subsequently, it aims to question the implied suggestions that, besides our living cultural background, we need particular descriptive knowledge to be able to appreciate art and that art appreciation involves advancing towards correct or perfect appreciation.

Indeed,in the traditional aesthetics we could say that the challenge in art is related to the intellectual challenge, as a play of intellect and imagination defining an aesthetic experience. But, as we could see in the quoted argument, the primary role of an opera was not understood as challenging the public. An intellectual challenge can be everything presented as an art composition demanding an intellectual effort. When faced with something we can not understand, we are challenged to try to understand it and play with possibilities. The disputable notion, argued by the mentioned article, was not that we should face the challenge posited by an art form but the challenge asserted by an explanation offered by a program essay. It was argued that the challenge is to accept the descriptive knowledge about art structured by others. Instead of playing with possibilities and eventually defining our own knowledge, we were instructed to face the "correct challenge," the one constrained by the translation of symbolism into proper linguistic correlatives - the correct meaning. In place of enjoying the challenge posited by an art form, we are to enjoy the linguistic platitude, the ready-made thoughts prepared by an expert. In other words, we are encouraged to fetishise our experiences and experience an opera as the product of kitsch pseudo-culture.

Translating the visual symbolism of an opera scenography into descriptive explanations would, supposedly, facilitate a better or more advanced appreciation of art. The argument was that our cultural background is not sufficient to allow us the appreciation of an opera without particular descriptive knowledge that should be provided by the program essay as a substitute for our own experience of active learning. Furthermore, the implied correctness of appreciation is supposed to be measured by the criteria of descriptive knowledge. Knowledge can subsequently advance appreciation towards the perfect appreciation. (Footnote: The fact that Peter Tregear seriously suggested that we could be able to reach the perfect appreciation is supported by his question as a response to another reader's post: Do we, an audience, really come to artworks (...) perfectly able to appreciate every aspect of them? )

Quantifying the aesthetic appreciation to suggest that descriptive knowledge (an explanation, if you will) can improve appreciation (to advance towards perfection in appreciation) is a silly idea implying Platonist teleology and the confusion of experience with knowledge. Indeed, our knowledge can benefit from explanations, descriptive art history or theoretical knowledge related to particular work of art. However, we should not think of knowledge as appreciation. Knowledge about art is welcome as long as we do not confuse it for the goal of an artistic statement. An explanation is neither a substitute nor the original behind the experience of artwork . (Footnote: In postmodern understanding, well framed by Derrida, it is always in the relation of similar to similar. As such, neither referent can claim a higher metaphysical or explanatory value beyond the immediate personal experience. ) The works of art are commonly not created for explanations but the experience. The descriptive knowledge is not in the same logical and physical category as the experience and can not be seen as an agent improving appreciation. (We could say that it could influence it and change it but not improve it) Likewise, the experience of descriptive knowledge about art should not be confused with the experience of art. Appreciating the ready-made explanations rather than the works of art is associated with fetishised kitsch experiences rather than aesthetic experiences. (Footnote: See for example arguments on kitsch by Hannah Arendt, Ludwig Giesz, Abraham Moles, Clement Greenberg and Thorsten Botz-Bornstein. )

Apples and pears should not be compared

Apples and pears should not be compared. The language of art history is quite a different framework from an aesthetic experience. So, speaking of the historic value of art is not the same as speaking about the value of an aesthetic experience. The first is the realm of logical discursive reasoning, and the second is the realm of mythopoetic experience. The point of the former is conceptual closure, and the latter is in the experience of searching for closure. We could say that the difference is similar to the difference between talking about sex and having sex. Indeed, it should not be strange if we insist that there should be different criteria for measuring the value of sex and the value of sex conversation.

In Kant’s terms, the domain of aesthetics is the experience of bringing faculties under the concept (where the accent is on the experience) and, in Derrida’s terms, it is not in the offered, but the ever deferred presence. In short, if you tell me what something is supposed to mean, you deny me the privilege to do and enjoy the search myself. In popular urban aesthetics it is called a spoiler since it is revealing something which you likely would have rather learned on your own. (Footnote: urbandictionary.com ) By providing knowledge, spoiler is not contributing to appreciation but spoiling the pleassure of personal experience.

An artwork should not be mediated by spoilers. It is not supposed to evoke, reflect or communicate answers and questions already existing in our culture, or narratives of a period, but to allow a personal relationship to an art object in a way to facilitate the play with possibilities and, eventually, come to questions of our own. As pointed out by Hannah Arendt, this experience has immense epistemic value in the merging of private and public spheres. Art is a way to feel the culture and make the public knowledge our own, over the conceptual closures initiated by us and not by descriptive knowledge offering linguistic platitudes distanced from individual experience.

In this sense, instead of disseminating knowledge by the referential linguistic function, like the language of the art history, art is supposed to create different experiences and, eventually, different meanings. In linguistics, it is referred to as the aesthetic function of language. (Footnote: A poetic function in Jakobson's terminology ) It is the realm of indeterminacy, metaphor and polysemy related to emotions. Aristotle called it the realm of possible, of mythos as opposed to reality and the language of logos. Alain Robbe-Grillet, for example, argued that to a modern novelist a novel is a way of finding out what he wanted to say. In other words, both for art creation and art reception, the challenge is not in communicating ideas but in the emotions following the process of search. (Footnote: Bachtinean postmodernists related these emotions to Augustine's voluptas and the poetics of carnival that, unfortunately, ended with the concept of entertainment supporting the corporate kitsch industry of contemporary neoliberal societies. ) In this sense the idea of the "correct interpretation" was in 1946 effectively criticised by Wimsatt and Beardsley as "The Intentional Fallacy".

Now, this is not exclusively a modernist notion. Lyotard reached to Kantian sublime to assert the suspended presence of meaning (logos, or deferred presence, for Derrida) as defining postmodern art forms. Even Deleuze was well aware that the point of art is in summing it up for yourself. (Footnote: Deleuze even assigned the same principle of knowledge by acquaintance (as sensing the difference and creating your own knowledge by setting new problems and subverting ready-made thoughts) by defining philosophy as the art of creating concepts )

The aesthetic experience should be understood in a hermeneutic sense, as a merging of horizons realised by individual experiences (as personal acquaintances with an art object) where private meets public, (Footnote: See for example the theory of reception and reader response criticism by Hans Robert Jauss and Wolfgang Iser based on Gadamer's hermeneutics. Contemporary literary criticism is in general opposed to classic intentionalism that commonly used to frame author's intention as ideas expressed by language he/she supposedly intended to convay. ) rather than propagation of discursive meaning. Thinking about narrative as a metaphysical presence by ignoring living individual experience is naive logocentrism. Likewise, the ideas of perfection in appreciation, the right questions supposedly asked by artworks, combined with the proper historical and social context are conceptual anachronisms from Plato’s idealist philosophy persisting in popular postmodernist art theory.

.

.

Art is not about knowing but the experience of learning

This writing is not an argument against descriptive knowledge of particular art, and it is certainly not a claim that knowledge will necessarily reduce the enjoyment and appreciation of Lohengrin opera. Rather, it is an argument against the implied logocentric idea that the enjoyment and appreciation of art are all about knowing instead of the experience of learning.

The problem is not in knowing art before facing it but in the implied idea that having an experience of art is all about knowing something. It is not about knowing (the closure) but about experiencing the process of learning. It is about the experience of our relation to the art, the performance rather than the conceptual sum total. The focus is on experiencing the search instead on finding the meaning. It is in personal engagement with the form and the experience of the play of our intellect and imagination.

That is why many modernist artists insisted that their works do not have meanings or that meanings are already present, integrated into the art form and can not be trans-formed into words. That is the sense of the famous statement by poet, Archibald MacLeish asserting that: A poem should not mean but be. The meaning was understood as a conceptual closure that should be avoided in poetry. Bacon pointed to the bias towards meanings expressed by words by arguing that, if artists wanted to say something, they would use words instead of painting. Derrida recognised the bias of the Western culture towards identity as linguistic meanings and ever-present matrixes of experience. He referred to it as logocentrism. Correspondingly, Wittgenstein argued: Why do you demand explanations? If they are given you, you will once more be facing a terminus. They cannot get you any further than you are at present. (Footnote: Zettel,315 )

For Wittgenstein, meanings are embedded in living experiences as the knowledge of game rules manifested by playing. It makes no sense to ask for meaning if you are already playing the game. Indeed, asking for the meaning may be an excuse to avoid playing the game. People who want to know the results of a game want to bypass the experience of playing. By looking for ready-made explanations, they want the impossible. They want the benefits of the game but avoid engagement in the game. And they are ready to persuade themselves that the benefits are linguistic correlatives. Psychology could frame it as evading intellectual and emotional efforts by heuristic jumping to conclusions. The experience of art involves a far more energy-costly challenge than the engagement promised by entertainment, which aims to maximise pleasure by saving energy. That is why it seems reasonable to see art as entertainment and ready-made meanings as the goals of art.

When we ask for the meaning of something we expect words as explanations. We do not expect another painting to be a meaning of a painting but a linguistic platitude – a ready-made thought expressed by words. It is always the case that words explain pictures and never the other way around. Pictures are commonly perceived as being about ideas and ideas are logos expressed by words – the ultimate perfect originals determining even the progress towards perfection in understanding of the ideas supposedly expressed by art.

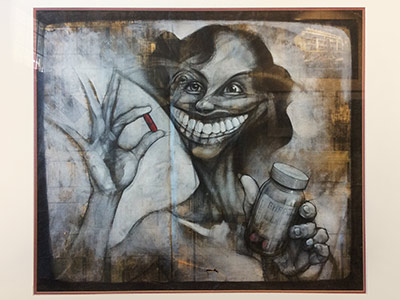

When we speak about finding the meaning it implies that we want to face the idea imagined as a linguistic expression. By focusing on the linguistic correlative (descriptive knowledge about particular artwork) we may fail to engage with the artwork itself. We might end with the popular notion that art is all about ideas expressed with words and are likely to end up enjoying the words (we take as the original idea expressed by an artwork) instead of the artwork. Many people have ready-made cliché responses associated with such ready-made thoughts; instead of enjoying art, they end up enjoying linguistic platitudes. In the language of communication theory, it is often referred to as the fetishisation of an experience specific to the language-biased pseudo-culture and the wrong education.

Postmodern Logocentrism

The ability to distinguish the experience of art from the experience of pseudo-cultural platitudes is critical for a healthy public sphere due to popular erroneous interpretations of postmodernist ideas about language. The widespread argument is that culture is narrative. A work of art is a text – a tissue of quotations. (Footnote: In popular, eroneous understandings, the term text is understood as asserting the priority of logos (the meaning expressed by logical-discoursive reasoning) and the affirmation of linguistic ideas expressed by an artwork. Paradoxically, the famous argument by Roland Barthes, The text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture, was directed against the traditional literary criticism's practicing of the intentional fallacy - the serch for the correct interpretation. See in "The Death of the Author" (1967). Martin Jay, for example, even interpreted the reference to text as a denigration of vision defining the stategy of French intellectuals. See Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought. ) And, since there is nothing outside of text in the realm of postmodern linguistic determinism, the physical reality is an intersubjective illusion experienced and shared by narrative. The narrative is, in the mishmash of modernist and postmodernist ideas, imagined as logical-discursive communication. It is about the transparency of ideas, referential function of language and endless linguistic correlatives. The belief behind the ubiquitous postmodernist logocentrism is that all meanings can be expressed by discoursive language. That implies the paradoxical notion that there is no qualitative difference between experiencing a concert and reading about it in an article like this one.

The problem of appreciation of art enslaved by logos is not in the existence of descriptive notes (explanations), but in the implied idea that reading the notes about art can substitute or improve the experience of art. It is like arguing that, since sex is the form of communication, reading about sex is a correlative of and even better than having sex. Supposedly, it is because the text is better expressing the correct idea about sex. Without our sex notes, we can have no sex. Well, a psychotherapist would likely suggest that sex is not about ideas and that it would be wise to forget our notes about sex while having sex. Arguing that reading about sex while having sex can improve our sex appreciation, just because of the postmodern belief that there is no substantial difference between having sex and reading about it, is highly disputable. We can not speak about improvement provided by having sex to reading about it since these experiences are not in the same category. We can speak about different rather than advancing experiences.

The suggestion that we need linguistic correlatives to understand visual cues of opera scenography is undermining our visual culture and encouraging the claims that words are, epistemically, more worthy than music and pictures. Like, there can be no knowledge without words, and words can substitute the experience.

Such arguments are flattering to an audience who attend opera for the wrong reasons.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment